We’re still spinning our wheels on “Portuguese politics part three”1 but since we began this series with part one, and continued with part two, we’ve come to understand there’s a whole other thing that’s happening Right Now that is both unrelated to what we’ve been writing about in these posts and yet so intertwined that we need to talk about it.

The European Union

Portugal is a member of the European Union (EU). Until about five minutes ago, we weren’t exactly clear on what that means. Perhaps, we thought, the EU is a bit like the Ivy League … a loose collection of institutions that play a few athletic contests a year against each other but otherwise operate largely independently. Or maybe it’s a bit more like, say, NATO, where members pledge to defend each other from enemy attack but, again, basically do their own thing day-to-day.

It turns out the EU is more than that.

Like, a lot more.

First and foremost, the EU is a collection of countries (not all of which are technically in Europe) that have crafted and agreed to abide by a common set of rules and regulations.2

There are seven main decision-making institutions in the EU. They are the:

The interplay between them is complex and an explanation of each of these is beyond the scope of this blog post.

Our focus today is on the European Parliament, to which each of the 27 member nations send representatives. This Parliament is one of two EU legislative bodies, the other being the Council of the European Union. The latter body, known officially as the Council and colloquially as the Council of Ministers, consists of ten different groups of 27 ministers each, one from each member nation. (For example, if there’s an issue about collective EU defense, the 27 defense ministers would meet to discuss it. And ministers of agriculture and finance would meet to discuss issues in their areas, etc.)

The Council writes legislation.

The Parliament meets as a body to deliberate on and pass that legislation.

The European Parliament

Elections for the European Parliament are held every five years and the composition of the body has been a bit of a moving target of late. The upcoming election will be the first since Brexit - 27 of UK’s seats were reallocated in January 2020 (46 were abolished entirely) reducing the number of seats to its current total of 705. That number will rise to 720 soon.

The Parliament has representatives from every EU nation, the number of which is proportional to the country’s population, while slightly overrepresenting the smaller nations. The current allocation is as follows:

The Parliament adopts legislation proposed by the Council in what is effectively a bicameral legislative body that has the authority to pass laws that can affect the day-to-day lives of each of the roughly 448 million people who live in and any of the businesses that operate in or with the EU.3

And it is this parliament that has created the need for a “post 2.5” in our series, because there’s a major election from June 6 - 9.

EU parliamentary elections

Every citizen of the EU age 18 or older (16 in four countries, 17 in one) - nearly 359,000,000 people - is eligible to vote, making these the second-largest democratic elections in the world, behind India.

Across the EU, interest in the election is high. Polling suggests a turnout that could exceed 70% in some nations.

So what are people voting for?

That is an excellent question with a slightly more complicated than expected answer.

In the US, every open seat - from local school boards and city councils through the president - is filled by a person who is voted for by constituents. Billboards and yard signs tout these people’s names for all to see. Newspapers publish profiles and interviews with the candidates who will sometimes appear on tv and debate their opposition. And voters line up on Election Day to check the box for the person of their choice, occasionally selecting someone who doesn’t identify with the political party the voter usually supports.

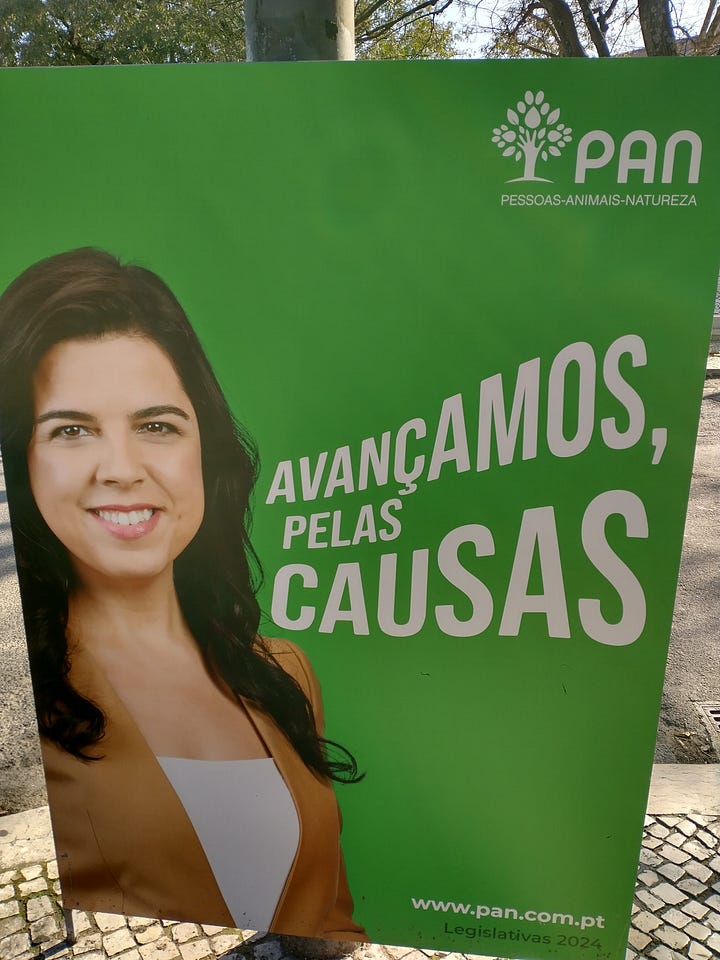

Here in Lisbon, there are plenty of political billboards. They’ve been all over the place for weeks.

Notice that these are all for parties (or alliances of parties), though, not people. EU citizens will be voting for their party of preference in June, not a candidate. The parties then send specific MEPs (Members of the European Parliament) to Brussels and France, where the parliament conducts its business. It’s slightly complicated and this article does a far better job of explaining it than we can.

To make matters more complicated interesting, the European Parliament has different parties than the ones in any EU country.

The parties from any given EU country align themselves with one of the European political parties, which are often called groups rather than parties.

So a Portuguese voter who generally backs the Portuguese center-left PS party will be hoping to see the European Parliament S&D group do well next month. Likewise, those supporting either center-right PSD or the slightly-farther-right CDS-PP,4 will be hoping for a groundswell of support for EPP.

But how am I to know which European group best represents my personal views, you ask? Turns out there’s an app for that. And in the name of research, Scott downloaded Adeno onto his Android phone - it’s free - and gave it a spin.

It’s helpful to be multi-lingual but certainly possible to get by using English alone. The instructions were in Portuguese. (This is likely because Scott switched his phone’s language to Portuguese some months ago.5)

The Modo clássico asks 100 questions organized into 10 themes to find the result that suits the respondent’s convictions. Scott was highly dubious about his ability to understand 100 questions in Portuguese but it turns out he needn’t have worried as the questions were in (probably AI-translated) English.

100 answers later, he learned that he matched most closely to the Greens (by a hair over S&D)6 but when he went to learn more about why, he encountered an obstacle he didn’t feel like trying to surmount.

Major issues in the election

The big question being asked in the run up to June’s election is How far to the right will the parliament swing? Consensus is that ECR and ID parties will both gain ground.7 Given the general overlap between their views, there has been merger talk. Were they to join forces, they would almost certainly become the third-largest group in the parliament. There appear to be enough points of disagreement, though, to make the alignment unlikely.

And here’s where the adage all politics is local may come into play. In Portugal, the far-right Chega has made its gains in part by positioning itself as the anti-corruption party. In general, far-right groups are also doing a better job of social media management than most other parties, reaching younger voters in particular via TikTok.

This article in The Parliament magazine does a good job of summarizing what each of the European Parliament’s groups say they stand for.

Issues here in Portugal

Portugal’s election will be on June 9. That date is controversial because it’s a long, holiday weekend - June 10 is Portugal Day, an important national celebration.8 Normally, that would be expected to suppress voter turnout. Given the closeness of the Portuguese national snap elections held in March,9 the upcoming EU races are being viewed as an extension of the previous contest, which could mean higher than usual turnout. What this will actually mean in two weeks will be a mystery until it’s over.

This is how Portugal’s 21 seats in the European Parliament are currently allocated:

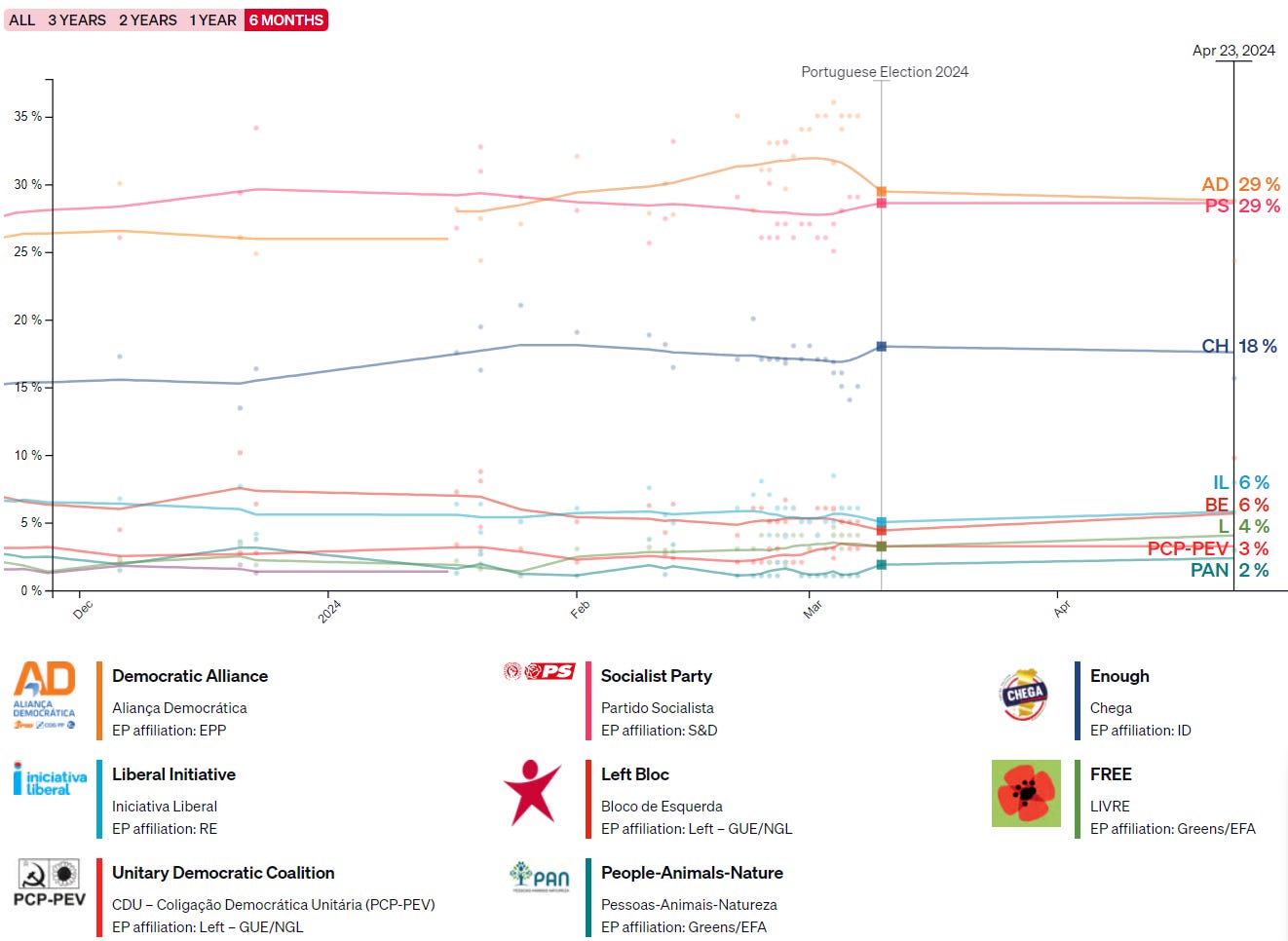

Polling suggests some changes are coming. For one thing, support for PS and PPD/PSD is basically even today but, more importantly, Chega, Portugal’s extreme-right party, didn’t even exist when the last European Parliament election was held in 2019.10

What to watch for

Polling in Portugal seems for now to be more accurate than what we’ve seen in the US of late. It’s a bit harder to judge how predictive a continent-wide survey might be but it does look a lot like the next five years will see a Parliament that Politico says will be “more Russia-friendly, less green and more Euroskeptic than ever.”

Overall turnout rate and the youth vote will be worth keeping an eye on. If The Parliament is correct, young voters will be turning out for the right next month.

We are living in interesting times.

That’s all for now.

Love from Lisbon,

Scott & Amy

Scott currently has ~175 tabs on that subject bookmarked in his browser.

For comparison, the US has 341 million people. In about twice the amount of land.

Spoiler alert for Portuguese politics part three, these two groups have formed an alliance in the current Portuguese government.

Go ahead, ask if that was a good decision …

To be fair, he lacked the proper context to fully understand many of the questions. And in entirely too many cases the differences between answers were subtle. It felt more like the SAT than a “Which Hogwarts house does your cat belong to?” quiz.

Chega’s MEPs will caucus with ID.

Which we’ll talk about more in Portuguese politics part three. Eventually.

Which we’ll also talk about more in Portuguese politics part three. Eventually.

Remember how in the last issue/episode/missive, you were able to drive into Spain as if you were driving from one US state into another? EU. 🙂 But, hopefully, you knew that by now 🙂

This freedom of travel, which doesn't happen between member and non-member states, but is guaranteed between the Republic and the North in the Good Friday Accords, is a huge sticking point in Brexit on the island of Ireland. Actually, I am just gonna stop here 🙄😀

Head-spinning layers of governmental involvement and oversight beyond the national level.