Most of the American immigrants we’ve met here cite - directly or indirectly - the political situation in the US as a reason for moving overseas. We’re in that boat as well, and we’ve felt some relief at not being in the seething cauldron of discontent on a day-to-day basis.

Politics in Portugal is not all rainbows and unicorns, though. Far from it.

While there is considerably less chance of an armed mob storming the parliament building or a domestic terrorist blowing up a Pingo Doce in Portugal, there are nonetheless some disturbing signs of late.

Before we get too much farther along, though, let’s make sure we’re all on the same page.

A Brief Historical Note

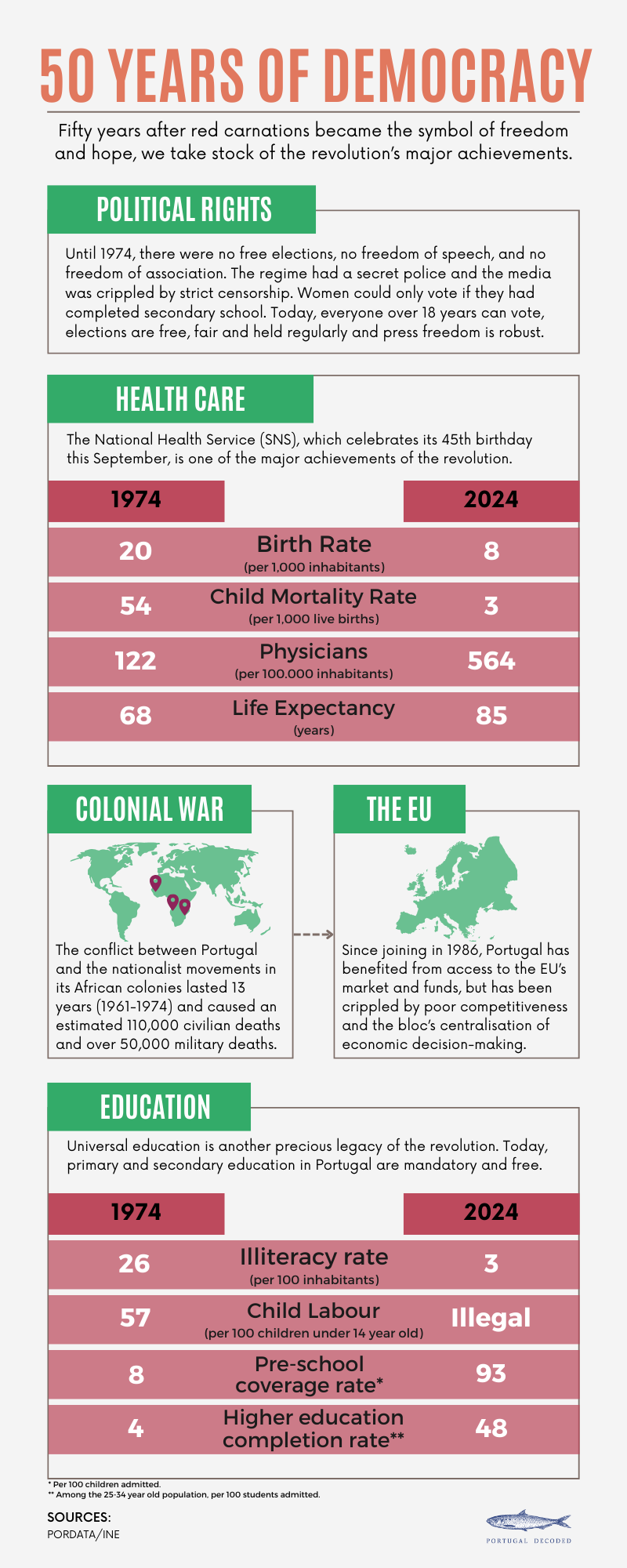

It’s important contextually to understand that Portugal was under a dictatorship called Estado Novo (“new state”) from 1932 until the famous Carnation Revolution on April 25, 19741, making it one of the longest-lived authoritarian regimes in Europe. While much has been written about the reign of António Salazar, what matters most for the purposes of these posts is that Portugal’s current representative democratic republic is quite young. Almost every Portuguese citizen of voting age either lived under the Estado or has a parent or grandparent who did.

The Basics

Like the US, Portugal’s federal government consists of executive, legislative, and judicial branches. This post will focus on the executive and legislative branches, with an emphasis on the legislative.

While the the executive branch in the US is headed by a president, Portugal’s prime minister serves as the leader of the government. Portugal does have a president as well, but his duties are different from those in the US.

An oversimplified way to view the roles is to see the prime minister as the face of the nation and the president as the wizard behind the curtain.

The president is directly elected by the people and appoints the prime minister - who is usually, but not always, the leader of the largest party in the previous election. The president also has the power to dismiss the prime minister and/or dissolve parliament if necessary.2

The prime minister represents the government to other countries, is answerable to the parliament and keeps the president informed via regular meetings.

Unlike the US, which has a bicameral legislature - the House of Representatives with 435 elected officials, and the Senate with 100 - the Portuguese legislative branch consists of one parliament, called the Assembly of the Republic, with 230 seats. These 230 seats are filled proportionally from 22 districts, 18 of which are on mainland Portugal, one each from the Azores and Madeira, and the remaining two from Portuguese living abroad.

And while the vast majority of elections in the US are won by Democrats or Republicans, there are currently nine different parties represented in the Assembly. There’s also a party-independent seat-holder and no fewer than nine other active groups without a representative in the parliament. For one party to govern without the aid of others, it must hold at least 116 seats in the Assembly.3 With so many parties to spread the votes around, that rarely happens. Consequently, legislators must usually work together to form a viable government.4

On January 30, 2022, however, there were early elections5 and the center-left Socialist Party (PS), led by 62-year-old incumbent Prime Minister António Costa, won an unexpected majority with 120 seats. This was the makeup of the body when we arrived in Portugal a few months later.

Names and Faces

While there are many parties with representatives in the Assembly, a quick glance at the graph above shows that after the 2022 election two had the most.

We’ve already mentioned the center-left PS, headed at the time by António Costa who was first elected Prime Minister in 2015. PS was founded in 1973, a year before the dissolution of Salazar’s dictatorship.

The center-right, or “opposition” party in 2022, is the Social Democratic Party (PSD), originally named the Democratic People’s Party (Partido Popular Democrático), hence the PPD/PSD designation on the above chart. This party was founded two weeks after the peaceful overthrow of the Estado Novo in 1974 and is led today by 51-year-old Luís Montenegro.6

Montenegro in 2024, age 51. In that same 2022 election that put the PS into a majority, there was some movement on the far right as a party called Chega (Portuguese for “enough”) began to gain momentum. In 2019, André Ventura - a charismatic, 36-year-old former football pundit - abandoned the center-right PSD to create Chega after losing a bid as PSD candidate for mayor of the city of Loures the year before. Chega (CH in the above chart) won 12 seats in the Assembly two years ago. That may not sound like much but three things are worth noting:

The party was less than three years old at the time.

It previously held just one seat, occupied by Ventura.

In that election it moved from being a fringe voice to the third-largest party in the Assembly.7

And we’d be remiss not to mention here the popular president of the Republic, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa. First elected on March 9, 2016, after running on a campaign of moderation and cross-party consensus, he was a former leader of the center-right PSD. He has formally suspended his party membership for the duration of his time in office.

In addition to the duties listed earlier in this post, the president “promulgates” all laws passed by the Assembly (without this official act, the law does not take effect) and has the authority to either veto a law or send it to the Constitutional Court to determine its constitutionality before doing so.

Rebelo de Sousa in 2017, age 69.

So now we’ve met the main characters and the stage is set.

When we arrived in Portugal in June 2022, the Prime Minister and his center-left party had control of the government. As long as they could keep their members in line, the PS could pass any legislation they cared to. And since this party operates like a normal entity without internal factions and squabbling (if there’s sufficient disagreement, members have plenty of other party options to join), things seemed poised to go smoothly.

Spoiler alert: things did not go smoothly.

The next post in this series will discuss what has happened since the 2022 election and look forward to what the coming months may bring.

That’s all for now.

Love from Portugal,

Scott & Amy

This is an important date in Portuguese history, the 50th anniversary of which will be celebrated in just a few weeks.

The Portuguese president operates as sort of a moderating power between the three traditional branches of government.

Assuming, of course, that all of the legislators holding those seats vote to pass each law in question. Which doesn’t seem to be an issue here.

This is a reasonably common, if sometimes unwieldy, arrangement. Avid news followers may recall that Israel had some trouble forming a government not all that long ago, a process which resulted in five elections in less than four years. Is Portugal heading down that road? Stay tuned …

Another thing that’s different from the US. While there are regularly scheduled national elections, circumstances occasionally dictate a call for an unscheduled early or “snap” election.

Who, spoiler alert, is now Prime Minister.

Granted it was a considerable distance from the second, but still.

This is a great summary of Portugal’s political system; the best I’ve read so far. I’m looking forward to your next post. Well done.

Great post. We’ve read about the election some, but highly value your inside perspective.