Wednesday morning we were startled by the sound of masses of children. Rua do Passadiço was filled with kids holding carnations, getting ready to march in one of the many parades around town. As I type this, the evening of 25 April, we’ve been treated to music and lots of chanting floating through our open windows. What gives? you say. I’m glad you asked.

We’ve mentioned that Portugal had a long-running dictatorship. Forty-wo years long. Fifty years ago, one of the most impactful changes in Europe took place here in Portugal. A military coup took over the dictatorship and installed a democracy. The most remarkable thing? It was essentially violence-free.1

Why was there a dictatorship?

Portugal was a monarchy for 771 years, until 1910 when a couple of hundred revolutionaries threw themselves a party in The Rotunda - a large praça or square - and refused to leave. Reluctant to be party poopers, the soldiers ordered to move them out said Nah. A couple of days later, the king cried Uncle and Portugal had itself a new government: the First Portuguese Republic.2

Sadly, this new government was not stable.3 It lasted 16 years and boasted eight different presidents, party infighting, and corruption. Not surprisingly, a military coup rousted them and installed the Estado Novo, or New State. Anti-communism / socialism / anarchism / liberalism / colonization, the government was conservative, pro-big corporations, nationalist - and very Catholic.

What was life like under the dictatorship?

Like any self-respecting dictatorship, the government boasted secret police who harassed, imprisoned, tortured and killed. They controlled the press and were big into censorship. Fear ruled as one never knew who was a member of the secret police, chomping at the bit to rat you out. Catholicism became the national religion and its tenets became law.

At this point, Portugal had not joined in the European fervor to get out of the colonialism business. The colonies of Angola, Portuguese Guinea, and Mozambique were clamoring for independence. Portugal said no way, José4, and began the 14-year Portugal Colonial War. The international community was giving Portugal serious side-eye. The people of Portugal increasingly chafed under the burden of this war - approximately 1.5 million Portuguese5 were drafted for terms of three years and citizens bore the cost of this long, drawn-out conflict on three different fronts.

What led to the Carnation Revolution?

In March 1974 the Deputy Minister of the Armed Forces, General António de Spínola, was dismissed. He had had the gall to write a book suggesting it was time for the war to end. Low-ranking officers - who supported Spínola, were tired of fighting these wars, and angered by a new law that gave conscripted officers the same rank as existing officers, just with much less training - formed the Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA), or Armed Forces Movement. Many members of this group were military who were stationed in Africa. Many, but certainly not all, were affiliated with the socialist and communist parties.

The main thrust was 1. An end to the Colonial War and 2. Regime change, in that order. Once the coup was started, the leaders broadcast an appeal for people to stay in their homes and remain calm. Instead, delirious citizens formed large, ecstatic crowds. The relatively simple coup had become a revolution.

What happened?

At 10:55 pm, the night before the coup, a radio station played Portugal’s Eurovision song, E Depois Do Adeus.

Whoa whoa! Hold the phone! Y’all talked entirely too much about Eurovision last year!

The playing of this song - which, by the way, tied for last in a field of 17 entries6 - was the first in two pre-arranged signals for the coup to begin. Twenty minutes after midnight, a different radio station played Grândola, Vila Morena, the second signal for the members of the Armed Forces Movement.

By 3 am, the military began the takeover. An hour and 20 minutes later, the Armed Forces Movement played on the radio an announcement that a coup was taking place. The airport had been taken over, two military headquarters occupied, two radio stations occupied, a TV station taken over, and a variety of troop movements begun. By 6 am, they laid siege to the the ministries, the civilian government, the main bank, and another radio station.

By 6:30 am, the government finally woke up and their troops moved out to meet the insurgents. When they got there, the two leaders had a confab, and en masse the government’s soldiers joined in the coup. By 9 am, a Portuguese naval frigate on NATO exercises followed government orders and took up position. When ordered to fire, though, they declined. Throughout the morning, the government had set up a command post, and sent troops hither and thither. Said troops went, but refused to engage. The Prime Minister had retreated to the headquarters of the Republican National Guard in the Carmo Barracks.

At 12:30 pm, troops arrived at Carmo and the siege began. An exultant crowd, shouting VICTORY!! VICTORY!!, gave the soldiers food and milk. By 2:30 pm, talks had begun to gain the surrender of the PM. At 4:15 pm, government police at Carmo fired on the crowd. At 7 pm, the Prime Minister and members of the government were removed.7

By 11:30 that night, laws were passed that forced resignations of the government leaders and abolished the secret police.8

It was all over but the celebrating. Oh, and creating a working government.

Reactions

A couple of weeks ago I got into a chat with a woman who had been 14 when the revolution happened. She recounted that it was a scary time, very uncertain, but also hopeful. Here is a link to an account by someone who was there. The Guardian was kind enough to reprint their article that they ran the day after the revolution. This sentence sums it up:

If it is successful the Portuguese military coup will probably prove to be one of the most important and far-reaching events since the war. - The Guardian 26 April, 1974

Effects

How does a country - bankrupt from 14 years of wars - shake off nearly a decade of corrupt and totalitarian government? With great turbulence. Two unsuccessful counter-coups - one by the right, and one by the left, a split in the Armed Forces Movement due to disagreements between the Communist Party and the Socialists, successful elections one year later to elect new representatives who rewrote the constitution, and finally, in 1976, elections to elect the new government (two years to the day after the Carnation Revolution).

The immediate and sudden withdrawal of all Portuguese administrators and military resulted in hundreds of thousands of Portuguese Africans coming to Portugal. Millions in Angola died as the country descended into civil war. East Timor was occupied by Indonesia, during which approximately 100,000 people died. Guinea-Bissau began a period of political instability that continues to this day. Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe had elections. Portuguese India was returned to India. Macau was caught in limbo: when Portugal attempted to return it to China, China said Nope, we’re in negotiations with the UN about Hong Kong, and we don’t want to piss them off. In 1999 it was returned to China.

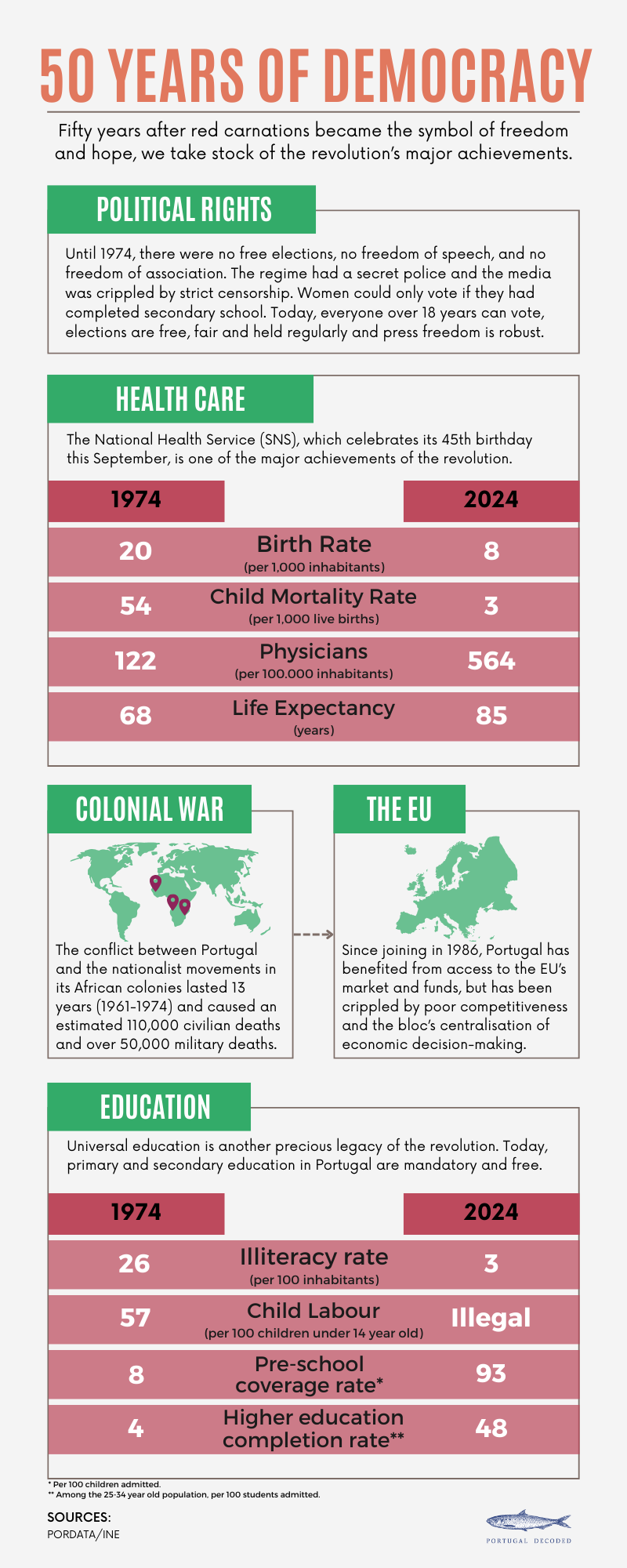

This chart does a better job than I could ever dream up of illustrating just how impressive Portugal’s accomplishments have been in recovering from the dictatorship.

Celebrations

This past weekend we were watching the tv to practice training our ears. The program we stumbled on involved reporters spread around the world, at celebrations and gatherings of Portuguese people living overseas, who gathered together to celebrate.

Here in Lisbon it was quite the festivities. Concerts and multiple parades celebrated this anniversary. We went to the main parade, down Avenida da Liberdade. At least, we tried. We’re quite confused by what actually occurred. The parade was scheduled to kick off at 3. We’ve experienced late-running parades here before, so we walked Josie down at about 4. The scene was as you see it. Hundreds of thousands of people filled the parade route, and the side streets were nearly as packed. Had we missed the parade? We had lunch with good friends who arrived at parade kickoff time, and only saw masses of people gathered in the parade route. They heard later that it took five hours for the demonstrations/crowds to thin enough for the parade to begin.

Being in this amazing crowd, I was very frustrated with my lack of fluency in Portuguese. Would that I could have talked with many of the people present who remember the time of the dictatorship and of this revolution.

Last note: why carnations?

One of the central gathering points for the military was in a flower market. Carnations were in season…. after one flower seller began handing out carnations, soldiers began sticking them in their rifles.

That’s all for now.

Love from Lisbon,

Amy

The secret police shot into a crowd and killed four people.

Wildly oversimplified.

Perhaps when the holiday for the 1910 revolution rolls around, I’ll write up a post about it.

Not that they didn’t try! Single-party governments, coalitions, executive presidents… you name it, they gave it a whirl.

José is the 7th most common name in Portugal.

To put this into context, the population of Portugal at the time was 8.8 million people. These are a bit apples and oranges - the war covered a 13 year time span, but the population statistic is only for one year. Still, hopefully it gives you a sense of the scale.

Arguably the most important song in the history of Eurovision, though.

Thanks to wiki for a great timeline of the day! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_Carnation_Revolution

Many thanks to wiki’s timeline of the revolution.

Great write-up! We are visiting here for two months and were very excited to be able to experience the celebration! We found out about it after visiting the exhibit at Aljude Museum. We asked our server at a restaurant afterwards and she wrote a list of about ten related events to see. She also spoke about the love and strength that one feels at the parade. We knew we had to go. The concert and display at Terreiro do Praço was phenomenal. They had vignettes of people (actors) relaying stories of being able to vote, the quality of life improvements, freedoms, education. And when certain songs were played … certainly during Grandola, Vila Morena, but other songs, too … the wonderful senior citizens, who knew life before and after 25.04.74 danced and waved carnations and sang along. Some of the exhibits we’ve seen (some may still be going on) include

10 Days the Shook Portugal exhibit at the Mercado do Forno do Tijolo

Manifestações de Liberdáde (photos from the Revolution) at Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa

Factum Eduardo Gageiro (he took phenomenal photos on 25 de Abril and also of the Alfama and Graça residents at Cordoaria Nacional

And all the carnations at the vertical garden at the Galeria Quadrum are blooming

The Parade! Yes! We were confused too. We finally started walking along the side street and figured out that it was almost a parade in reverse. Where the parade participants are standing and the audience walks by them instead of visa versa. A volunteer at the 10 days that shook exhibit had told us that she walks with several different groups at the parade. At the time I wondered how she could do that … the parade route isn’t THAT long. But then at the event, it made sense how she could switch between groups … none were walking very fast at all.

Oh I have written so much but one more story: We had gone to the São Jorge castle on the prior Sunday to make red paper carnations … they were having a little workshop to fill a plaque with them. I decided to make some to hand out to people at some of the restaurants we’d been frequenting. So I did, and I carried them around in a bag. I was a little embarrassed at first since they were paper and not “real ones”. But, on the way to the concert, we heard Grandola, Vila Morena being played and walked over to where the music was coming from. It was a restaurant we weren’t familiar with. It wasn’t open yet but the owner was setting things up. I walked up to him (totally out of my comfort zone) and offered him a red paper carnation. I said Can I give this to you? He gave me the biggest most sincere smile and said Yes! Do you know what it means? I said Yes! It’s for the 25 de Abril Revolution and this is the 50th Anniversary. That made him smile even wider!

After that I had no reservations about my paper flowers. I gave a bunch to various children … I always asked the parent first, to be mindful, and they always said YES and nodded encouragingly. They were all so nice to this strange American woman giving out paper carnations.

I have been enjoying your very detailed posts! Thank you for all the research you do and the insights you share. Much appreciated, for sure!