We’ve never lived in an environment as multi-national as this one. Just walking down the street we’re likely to hear snippets of conversation in many languages.

We’ve been mentally using the analogy of buckets to categorize what we hear.

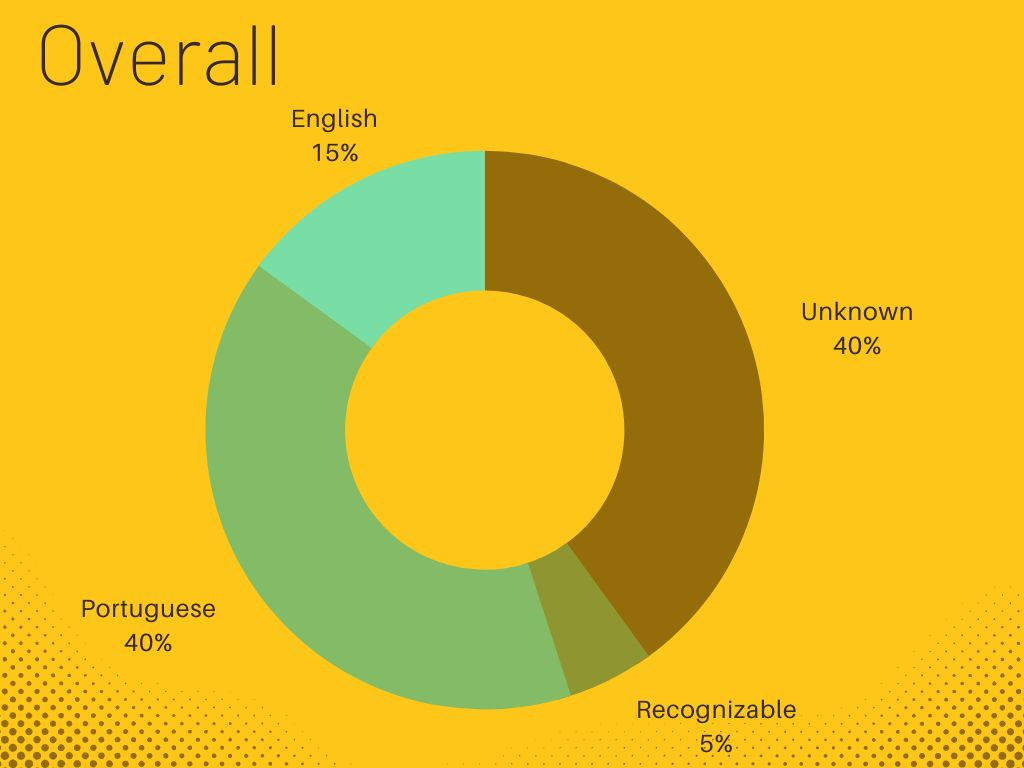

The English bucket is large and varied. We routinely encounter at least three separate accents from England alone, for example. We’ve also heard Scottish and possibly Welsh inflections and Scott recently played some board games with an Irish immigrant. Once, we overheard two Aussies at Continente discussing the merits of a variety of pre-made hamburgers. (They may have been Kiwis, actually; hard to tell.) While we’ve run into American accents as well – almost entirely the flat “news reporter” style like ours; no Texas twangs or Southern drawls yet (though we did hear a good, solid Bronx version not long ago) – those have been among the smaller contributions to the English bucket.

In our experience, the lingua franca of expat gatherings is English. Consequently, our English bucket is mostly filled by accents from a global sampler of non-native speakers. The Dutch speak English with an entirely different inflection as do French, Spanish, Germans, Italians, Ukranians, Russians, Poles … the list is seemingly limitless.

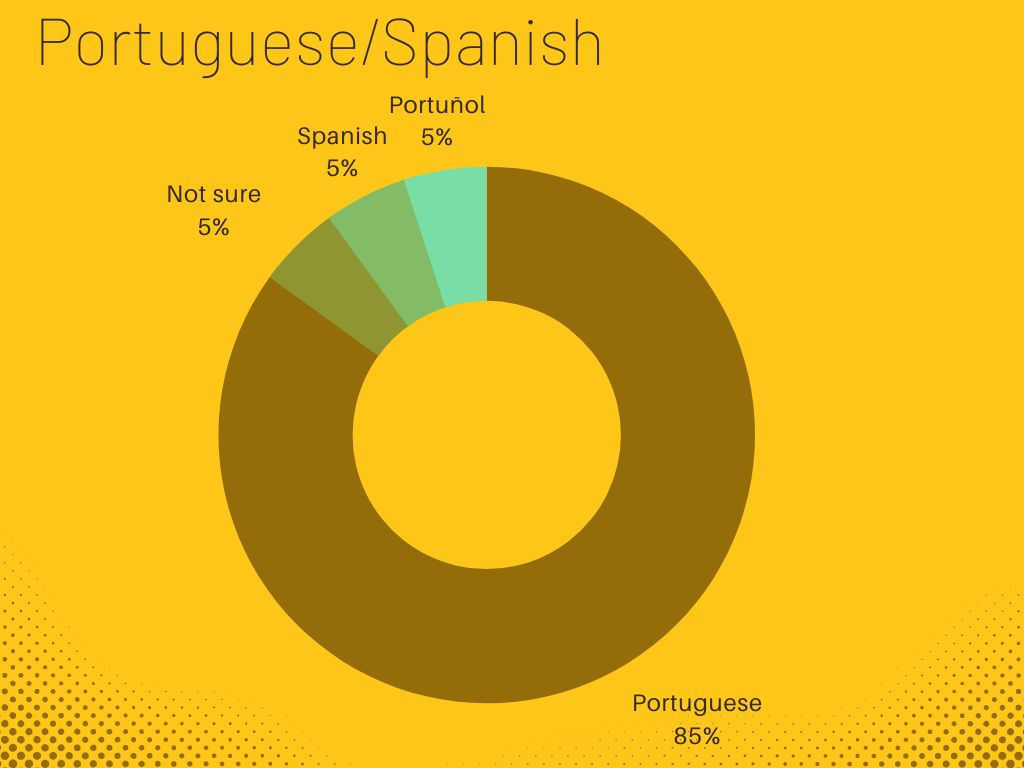

Naturally, there’s a lot of Portuguese spoken out and about – we do live in Portugal, after all. (Allegedly, natives of different parts of the country pronounce the same words slightly differently, but it’s going to be a bit before our ears can pick up that level of subtlety, we suspect.) There are other languages we recognize like Spanish, German, and French. These don’t pop up as much as we’d have though, though. Spanish speakers likely won’t fit in seamlessly here. Scott is an involuntary practitioner of Portuñol, defined by Wikipedia as an “unsystematic mixture of Portuguese and Spanish,” and judging by the number of YouTube videos we see by Portuguese teachers, he’s not the only one.

There is also a sizeable bucket of “no clue what language that is” overheard in grocery stores and on sidewalks as people speak with their companions or into cellphones. (Some of these sound like Op, a made-up language from The Big Bang Theory.)

So while there is plenty of English spoken here in Lisbon, there’s also no guarantee we’ll share a common language with anyone we randomly meet.

All of this has implications. For example, when walking down a crowded milk and egg aisle and need a little more space to get the hand cart through, should we say, “excuse me” or “com licença,” the Portuguese equivalent? And when Scott stumbles through, “Desculpe, eu não falo português muito bem. Fala inglês?” (“Sorry, I don’t speak Portuguese very well. Do you speak English?”) on the phone or when speaking to a store clerk, nothing really matters except the final word of that phrase. All someone needs to hear is inglês, or español, or francais, or whatever – the recipient can’t respond helpfully until they know what language to use. In fact, we’ve been the “recipient” on multiple occasions. And the request is often very simple: “English?” It gets the job done, even if lacks a certain elegance. This is Amy’s preferred approach. (Scott has employed a “why use one word when nine will do?” philosophy for nearly 50 years. Change is hard.)

This dance of a multitude of languages has larger effects as well. It’s intimidating to try and speak to strangers for anything unless absolutely necessary. Small talk while, say, standing in line is basically out the window. For Amy, who has a tendency to want to help anyone who looks in need of assistance, it’s particularly hard. While she’s a pro at non-verbally communicating concepts like, “I like your bracelet/necklace/hair,” trying to give directions to a lost tourist is an entirely different matter. Scott recently had an encounter with a suitcase-toting woman on the street that began this way:

Tourist (uneasily): Fala português?

Scott (uneasily): Um pouco.

Tourist: Do you speak English?

Scott (relieved): Yes, I do.

Tourist: Oh thank goodness! Do you know how to get to this address from here?

Fortunately, people are generally willing to help. Store clerks have applauded our attempts to speak our NIFs em português. Pharmacists respond in English to questions awkwardly asked in their native language (doubtless knowing that while we may be able to fumble out an approximation of the right words in a query, understanding the reply is an entirely different matter). And when people learn we live here and aren’t just getting back on a plane in a few days, they brighten and encourage us to keep at it.

We know multiple expats who’ve been living here for years who have made very little effort to learn Portuguese. It’s not necessary.

It is, however, quite helpful and potentially quite rewarding so we’ll keep at it.

I love that you are learning the language! Your experience there, no matter how long you stay, will be so much the richer for it! Plus you won't be the stereotypical Americans who expect everyone to speak English even when they can't speak any other language themselves. Go you!

I applaud you for trying. I don't think I would be able to do it.