A note, a box, and a rabbit hole

Amy's taken over a couple of times recently. Scott's turn now. (No political rants. I promise.) (53)

It began, as many good adventures do, with a note:

It was written by Paulo, the friendly pharmacist at the bottom of the hill, after I inquired about the vacation he took at the beginning of December. Turns out he’d gone to see family in Aveiro, a north/central Portuguese city known for its canals.

One of the side benefits of the annual family gathering for Paulo was that he ate too many doce de ovos, sweet eggs. While available year round, these are particularly common in parts of Portugal around Christmas. Paulo was adamant that they are his favorite seasonal delicacies. (“I don’t drink. I don’t smoke.” Sounds like they’re his only vice. And that he and I have much in common.) I, always willing to indulge my sweet tooth, asked for more information: Are they chocolate? No, they’re not. Then he wrote the note for me and the conversation ended.

Last week, on a post-Christmas markdown table at our favorite grocer, Pingo Doce, I spotted something that sounded vaguely familiar so I made an impulse purchase (no dairy involved, yay!).

As sometimes happens in the Herrfield-Redling home, the box hung out on the kitchen table for a few days and one morning I glanced at it idly while eating breakfast and something caught my eye. See if you can guess what it was. I’ll narrow it down for you:

I’ve not been in the presence of many things that have been in existence “since 1502” so, curiosity aroused, I gave the box a closer look. It only got more interesting on the back:

Only four sentences yet so much to unpack:

“. . . ancient Portuguese gastronomic references.”?

“ . . . used as a medicine . . .?”

“ . . . extinction of the convents . . .”?

“ . . . IGP certification . . .”?

There’s a lot going on in this little box of holiday treats.

To the interwebs!

As so often happens, a little casual googling soon took me down a rabbit hole. Some hours later, here’s a summary of what I learned.

First of all, it appears that centuries ago convent nuns used egg whites to starch and/or clean their habits. Rather than waste the egg yolks, they appear to have added sugar (the recipe most commonly given is basically “combine a bunch of egg yolks with half their weight in sugar”) to create possibly a variety of confections, of which Ovos Moles de Aveiro is perhaps the most famous type. These were sold to raise money to cover convent operating costs. (If this sounds vague, I imagine that’s because origin stories can get a little hazy after 520 years.)

While the “shell” of these soft eggs looks temptingly from the photos on the box like white chocolate, it’s clear from the ingredients list that it isn’t. In fact, the wrapping is essentially a soft communion wafer. (Never having taken communion I can’t vouch for the flavor similarity but it tastes as bland as a combination of wheat flour, water, and vegetable fat suggests it should.)

The specifics of how these delicacies were created were closely held by the nuns for centuries, until the establishment of the First Portuguese Republic in 1910. The First Republic is a 16-year bridge between the 5 October 1910 revolution overthrowing the governing constitutional monarchy (goodbye, Kingdom of Portugal) and the 28 May 1926 coup d’état that ushered in a 48-year dictatorship (hello, Antonio Salazar). During that brief, turbulent span, Portugal was governed by 9 presidents(!) and a whopping 44 prime ministers.

With that level of turnover at the top, it seems like the continuity of specific policies would suffer. One thing they all seemed to agree on, though, was that the Catholic church had too much influence. The Wikipedia article understates the atmosphere as “intensely anti-clerical.” And while a bunch of other stuff happened, what’s most relevant to our little treat box is these two sentences:

On 10 October—five days after the inauguration of the Republic—the new government decreed that all convents, monasteries and religious orders were to be suppressed. All residents of religious institutions were expelled and their goods confiscated.

The nuns passed their recipes to women outside the convent and ovos moles were secularized.

Fast forward to 1992 and the European Union (EU) passes legislation “to promote and protect names of agricultural products and foodstuffs.”

According again to Wikipedia (yes, I support Wikipedia financially):

The purpose of the law is to protect the reputation of the regional foods, promote rural and agricultural activity, help producers obtain a premium price for their authentic products, and eliminate the unfair competition and misleading of consumers by non-genuine products,[3] which may be of inferior quality or of different flavour.

An excellent example of the above law is the New Year’s Eve staple champagne. (Happy New Year, everyone! All the best to you in 2023!) There are many types of sparkling wine, but anything labeled “champagne” must by this law be from the Champagne wine region of France and have been produced using “specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, specific grape-pressing methods and secondary fermentation of the wine in the bottle to cause carbonation.[2]”

Other well-known products protected by these regulations include a whole mess of cheeses (Roquefort, gorgonzola, feta, Parmigiano-Reggiano, camembert, and many more) and cognac.

On January 30, 2006, an application was filed to obtain Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status for Ovos Moles de Aveiro. I am 100% serious when I say the application is riveting reading. I strongly encourage you to check it out (click here).

Highlights include (but are far from limited to):

There are documents showing that, in 1502, King Manuel I granted 10 ‘arrobas’ of Madeira sugar per year to the Convent of Jesus in Aveiro for the manufacture of confectionery products in the convent, which at the time was used to help patients during their convalescence.

Sugar. It does a body good.

The traditional maize used in chicken feed no doubt has contributed to the quality which distinguishes the product resulting from it.

You are what your chickens ate.

and

The temperature and the humidity of the ria are also propitious to the manufacture of Ovos Moles de Aveiro and the wafer, giving it the appropriate and long-lasting plasticity which is impossible to reproduce outside the region.

Bringing eating local to new heights.

Spoiler alert: the application was accepted and on what I read to be 27 April 2009 Ovos Moles de Aveiro was granted the right to bear this seal:

(In 2015, the application was amended - again, riveting reading - to allow:

using chocolate as a coating,

the mechanical separation of egg yolks from the whites, and

“the introduction of cooling using temperature-reducing equipment” - which was justified, in part, by the fact that “a panel of tasters who are experienced in sensorial analysis . . . checked that these variations do not alter the distinguishing characteristics of the product, with the quality remaining the same.”)

Amazing stuff, these smooshy little ovos.

Still unresolved was the basic question of whether these are, in fact, the items Paulo had mentioned so many weeks ago. Is ovos de doce a generic term (“cookies”) and Ovos Moles de Aveiro a specific type (“Oreos”)? Or are we talking about two different beasts here? The information online was unclear. Ovos moles translates to “soft eggs” and ovos de doce to “sweet eggs.” These happen to be both soft and sweet. What’s up with that?

Back to the farmácia!

I showed Paulo the box and many words came at me. (Paulo, bless his heart, gives me more credit than I deserve for my understanding of Portuguese.)

Eventually, it turns out that, yes, my box contains the champagne of sweet eggs.

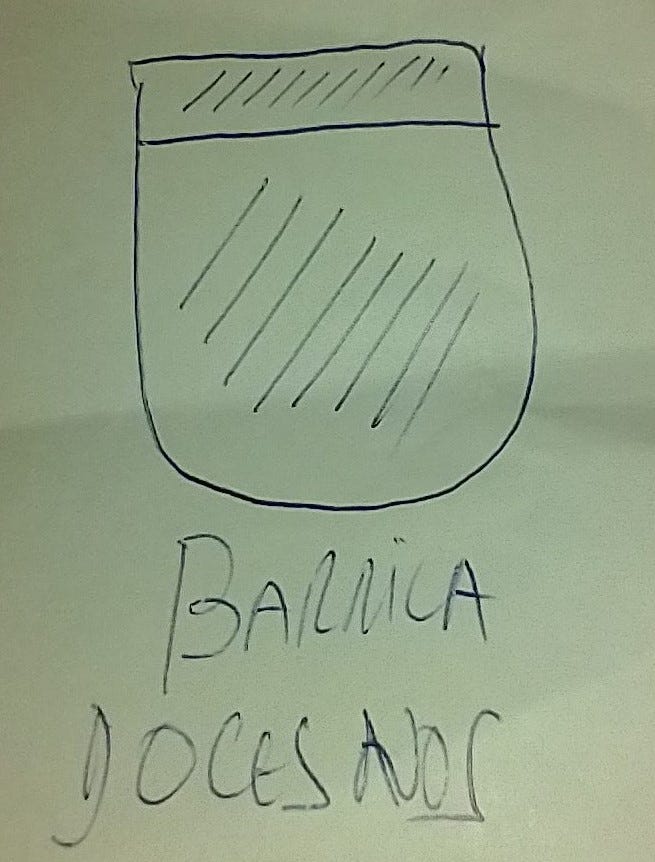

There is, apparently, a fancier kind of sweet eggs that involve a barrel in some way. The barrel version, evidently, are both the kind of eggs Paulo asked his grandmother for daily when he was a child and also more expensive than the Ovos Moles de Aveiro I purchased for 3,49€ a half dozen. Now, he prefers the ones from Aveiro. He also wrote me a new note:

More research for another day, I presume.

That’s all for now.

Love from Lisbon,

Scott (& Amy)

P.S. Want to know how these taste? Come visit! We’ll find you some. I won’t argue with the chance to eat more :-D.

I have a huge sweet tooth, so of course I tried these when I was in Aveiro last year. They're good, but so sweet that one every now and again is sufficient for me.

Really fascinating! Wish I could try one. Always interested in the foods of other countries. This one sounds really unusual, can't believe it survived so long. What does the coating taste/mouth feel like? You two write so well about your experiences. My friends like your posts also. Keep those posts coming!